On the internet today, all our web sites need a strong, secure HTTPS setup, even the most basic static sites. This is part two of a series on how to set up Nginx securely.

When we left off after part 1, we had a server with a valid, signed certificate, but it was using the default Nginx configuration. This configuration is far from optimal.

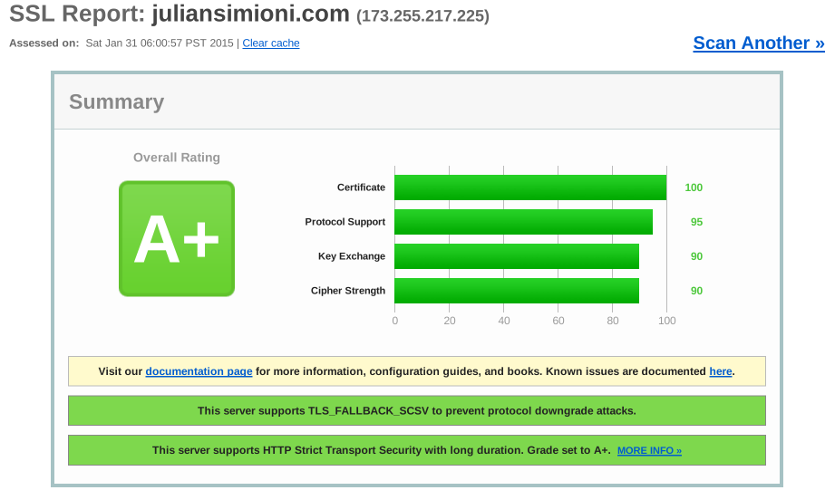

At the end of this post we’ll have a secure HTTPS configuration on

Nginx that scores an A+ rating on the SSL Labs report. We’ll even do a few extra

tweaks that improve performance and user experience.

In addition to the descriptions and code snippets here, I’ve compiled a ready to go SSL configuration file for Nginx, a nearly ready to go example site configuration file, and a complete list of all the sources I used while researching for these articles, and posted them for anyone to use freely on Github.

Disable SSLv3

By default Nginx still enables SSLv31, which has been vulnerable to the POODLE attack since October 2014. The only browser that doesn’t support newer protocols out of the box is IE6, and even it can be configured to use TLSv1, so there’s no reason to support SSLv3 anymore.

SSL Labs rightly limits your server’s SSL score to C if SSLv3 is enabled, so this is the first thing to change.

1 2 3 | |

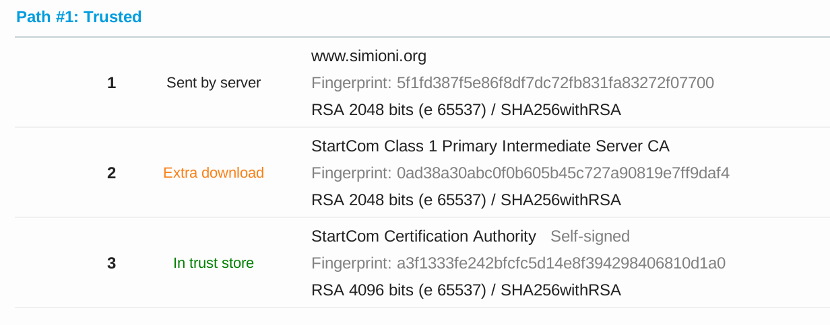

Send the Entire Certificate Chain

Browsers use root certificates from Certificate Authorities to determine which server certificates (such as the one from your website) should be trusted, but there’s almost always an intermediate certificate. To be sure your server’s certificate is valid, browsers need to know about this intermediate certificate.

Of course, browsers can find and download these intermediate certificates, but this slows down the process of connecting to your website, and makes the whole process more complicated giving attackers more surface area to exploit.

It’s much better to simply configure Nginx to send this intermediate certificate along when users first connect. In fact, your SSL score is capped at a B if you don’t.

Your Certificate Authority probably provided you with links to download your

intermediate certificate, so once you’ve found it, put it somewhere safe on

your server, and tell Nginx about it like this, and then make a new file

that concatenates your certificate and the intermediate certificate together.

Then tell Nginx about that one like this2:

1 2 | |

Ciphersuite Configuration

The SSL/TLS protocols actually don’t provide any encryption by themselves. Instead, they simply allow a server and client to agree on and start communicating via a channel that could have one of any number of encryption schemes.

Your server and a client will use SSL/TLS to agree on a combination of four things: key exchange algorithm (how to safely share encryption keys between the server and client), authentication (to make sure only the intended sender/recipient are communicating), encryption algorithm (actually encoding the messages so no one else can read them), and message digest algorithm (to make sure the message was not tampered with or corrupted).

There are many of each of these algorithms, all with varying features, performance, cryptographic strength, and browser support. Many of the algorithms have known weaknesses that make them unsuitable for use today. Using the latest version of a browser is usually enough to protect an individual user but, unfortunately, a lot of older browsers have insecure defaults.

The goal of cipher suite configuration is to ensure compatibility with as many browsers as possible, without compromising security or, to a lesser extent, performance.

This will be done by setting a configuration string that OpenSSL understands in our Nginx configuration. To keep thing simple here’s the relevant configuration lines:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

Now I’ll explain the rationale that went into crafting it.

Make the server choose the ciphersuite

Many browsers, especially old ones, will make poor ciphersuite choices on their own. The first directive ensures your server will choose from the list of ciphersuites supported by both the browser and server.

Disable null and low security ciphersuites

Strangely, it’s possible for SSL/TLS to use no encryption if configured improperly. Fortunately it is easy to disable this. OpenSSL also has its own internal list of ciphersuites with known low security, and disabling those is a good starting point.

Disable insecure algorithms

Some algorithms have known or suspected vulnerabilities, and we can disable or limit their use where appropriate. The following algorithms in particular should be disabled:

MD5: completely broken, still common

The MD5 hashing algorithm is commonly used but has had known weaknesses since 1996, only 4 years after it was introduced. Today, MD5 is famously vulnerable to collisions, especially with GPUs. It simply isn’t safe to use any more.

RC4: former poster child, recently tarnished

The RC4 cypher is also commonly used, and until recently was widely recommended. However, information revealed by no less than Edward Snowden himself has suggested that it’s possible the NSA has the ability to break RC4.

Combined with research showing theoretical vulnerabilities in RC4, the possibility that there are working attacks against RC4 in the wild is too plausible to ignore. Microsoft has issued a security advisory to disable RC4, and the IETF is drafting a memo to require clients and servers never use RC4.

SHA1: rapidly approaching affordable attacks

In part 1 we generated a certificate request using SHA256 instead of SHA1. For the same reasons, we also have to disable ciphersuites that use SHA1 as the hashing algorithm. No attacks against SHA1 have succeeded as of today, as far as we know, but it probably won’t be long.

Disable little-used ciphers

These are not common, and disabling them just simplifies things and reduces the surface area for attacks3.

Support perfect forward secrecy whenever possible

Perfect forward secrecy allows a secure connection to use encryption keys that are custom generated for that specific session. The security advantage this provides is incredible: even if the private key for a server is compromised, none of the messages sent to that server in the past can be decoded.

Furthermore, even if an attacker manages to successfully compromise a session key used by your server, they only gain access to a single session. This increases the cost, and decreases the reward, of attacking communication with your server.

A great recent example of this is Heartbleed: with perfect forward secrecy, the Heartbleed vulnerability can only expose individual sessions. You’d still have to update your server’s private key, but almost all user data would be safe even if your private key were exposed.

Most reasonably modern browsers, with the notable exception of IE8, support key exchange algorithms with perfect forward secrecy.

There is one additional configuration change that needs to be made to keep PFS

ciphersuites secure. By default Nginx will generate 1024-bit RSA keys for PFS

ciphers, but that can be overridden. Use the configuration changes below and be

sure to use openssl to generate the 2048 bit keys (it can take a few minutes).

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Optimize for performance where appropriate

Despite some algorithms occasionally being found vulnerable, modern browsers actually support a comprehensive suite of extremely powerful security tools. All four algorithms specified by NIST for Suite B cryptography , including AES and SHA2, are currently supported by a good portion of the browsers in use today.

Many security experts consider that using the longest key lengths currently supported does not have any measurable impact on security, and simply reduces performance4.

A common configuration that takes this into account is to support these most

secure variants, but prefer more reasonable key lengths. For example, the

configuration above supports both the ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-SHA384 and

ECDHE-ECDSA-AES128-SHA256 ciphersuites, but prefers the shorter key length

variant. Both provide excellent security with no known attacks. This makes the

default for most users secure and reasonably performant, but allows users to

demand the most secure ciphersuites if they so desire.

Enable HSTS

Many concepts in security involve correctly implementing a specific, precise procedure like a cryptographic algorithm to achieve a mathematically proven level of security. HSTS is not one of them.

Enabling HSTS simply tells browsers not to make any plain text requests to a server ever again.

In theory, this provides no benefits over a server properly configured to require a valid HTTPS connection for all resources, at all times. In practice, HSTS protects against a huge number of configuration errors that are easy to make.

It’s also easy to implement: all that is required is for the server to send a valid HSTS header with each HTTP request, and the browser will do the rest.

1 2 | |

This tells browsers to avoid plain HTTP requests to your server and all

subdomains for one year. It’s perfectly reasonable to remove the

includeSubdomains clause if not all your subdomains are ready for HTTPS.

Note that by enabling HSTS, you are essentially promising to browsers that your server will correctly respond to HTTPS requests until the header expires. This means its probably not something that should be enabled on day one of an HTTPS roll out.

Once you’re comfortably set up running HTTPS with no problems, you can also submit your site for HSTS Preload, allowing the latest versions of popular browsers to ship already knowing your server expects only HTTPS requests. This is incredible: modern browsers will never make even one HTTP request to your server.

The security benefits of HSTS are profound enough that SSL Labs requires it as the final prerequisite of an A+ SSL rating.

Improve Performance

Finally, there are a few more configuration changes that should be made to improve performance. As far as I know these either have no detrimental impact on security, or actually help improve it.

Set up OCSP Stapling

Before a browser will connect to a server using HTTPS, it has to check if the certificate the server is using is still valid. An upgrade or response to an attack could cause a certificate to be revoked, and its important to know about it.

Without further action on your part, every browser connecting to your server will have to pause when first connecting to ask an OCSP server for the latest revocation information for. OCSP stapling allows your server to do this ahead of time. The OCSP responses are signed by your Certification Authority, so browsers will be able to trust them, even if they come directly from your server.

This also cuts down on traffic to OCSP servers(a nice thing for you to do), and protects your server against unexpected interruptions because of downtime or denial of service attacks against your OCSP server.

1 2 | |

Support SSL Session Caching

By far the biggest concern when moving to HTTPS is performance: both extra load on servers, and slower page load times on the user side. By large, the overhead for an established secure session is not significant anymore.

However, the process of initially connecting via HTTPS involves many more round trips between client and server than HTTP, so there is still definitely a noticeable impact on page load times.

With that in mind, it makes sense to cache SSL sessions for at least a few

minutes, so that users only have to pay that cost once. Nginx is almost

configured correctly out of the box to do this. The only change needed is

setting a size limit for the session cache. The actual timeout is specified with

ssl_session_timeout, which defaults to 5 minutes. The 10MB cache size limit is suggested by

Nginx’s own HTTPS configuration guide:

1 2 3 4 | |

Resources and Thanks

I hope this guide can be considered comprehensive enough to be useful, but I would be lying if I said it was even close to covering everything. Security is a complicated, rapidly changing challenge. With that in mind I want to call out some of the best resources I’ve found both to provide more information and thank the authors of these great works.

- Eric Mill’s Switch to HTTPS Now, For Free, which first set me down this path

- SSL Lab’s SSL/TLS Deployment Best Practices - a really great and understandable deep dive

- Mozilla’s extremely complete Server Side TLS wiki page

- The Nginx blog has an article about POODLE, suggesting that everyone using Nginx disable SSLv3, so hopefully the default will change soon. ⏎

-

Many tutorials, like Eric Mill’s Switch to HTTPS Now, For free suggest performing something equivalent by concatenating the root certificate, intermediate certificate, and your server’s certificate together into one file. This works just fine, but I prefer keeping the files separate for clarity. Use whichever method works better for you.I asked about this on the <a href="http://forum.nginx.org/read.php?2,256613,256621#msg-256621">Nginx mailing list</a> and it turns out this works, but only by accident, and may break in future versions of OpenSSL or Nginx at any time. Use the standard concatenation method. - Some of these ciphersuites are more common in a few contries, and if you’re serving traffic to primarily one of them, it may make sense for you to enable them. ⏎

- For the same reasons, I don’t believe it makes sense to use certificates with 4096-bit keys, 4096-bit Diffie-Hellman key exhange parameters, or similar changes. You can actually improve subscores of your SSL score using them, but it will come at a performance cost. ⏎